Gingery Lathe

In the spring of 1998 I ordered the Gingery series of books on how to build a metalworking shop from scratch. I started with a 5 gallon steel bucket lined with firebrick mortar for a foundry. Fine sand from the bottom of a Virginia trout stream mixed with bentonite clay for a binder was my molding sand. Scrap aluminum was used for melting stock. My woodshop was already fairly well equipped and I had the experience of building a wood lathe behind me, so I felt that I was up for the challenge of building some metalworking equipment. To me, this was one of the great learning experiences of a lifetime. It is a fascinating experience to build a precision machine tool from scratch. It is also quite laborious. In addition to lifting, flipping and ramming up sand molds, tending the charcoal foundry, pouring 1400 deg aluminum and hacksawing, you have many hours of filing and scraping to look forward to. I spent about 24 hours just scraping the bed flat. Your hands will also be dyed Prussian blue as you scrape the castings, blue them, rub them over a surface plate and scrape some more. You will very quickly understand and appreciate why precision machinery costs what it does, and you may wonder why it does not cost more. In my opinion, the real incentive for starting down the Gingery road, should be for the education and experience. When you have a machine or two under your belt, you should be able to design and build nearly any machine or mechanism that does not require more than a quart of metal in a single part (See the IsoBevel Grinder). You will also understand how to design patterns and have some ability to predict where you will need risers when making a new part. In any case, I finished my Gingery lathe, about 9 months after I started (working on it in the evenings and weekends). It works as advertised and turns on the faceplate and centers quite nicely. It would be nice to have an array of chucks to reduce set-up time. I have turned many steel and aluminum parts on the lathe; however, I have not successfully turned brass. Brass usually sets the machine to chattering. Perhaps it's the bit or the limited rigidity of the lathe. The aluminum lathe components do not have the mass or rigidity of a commercially made lathe. For this reason, I would suggest that if you want a lathe that is easy to use, allows for quick set-ups and has that all-important quality of tremendous rigidity, buy it. If you are interested expanding your horizons and in the education and experience, build it.

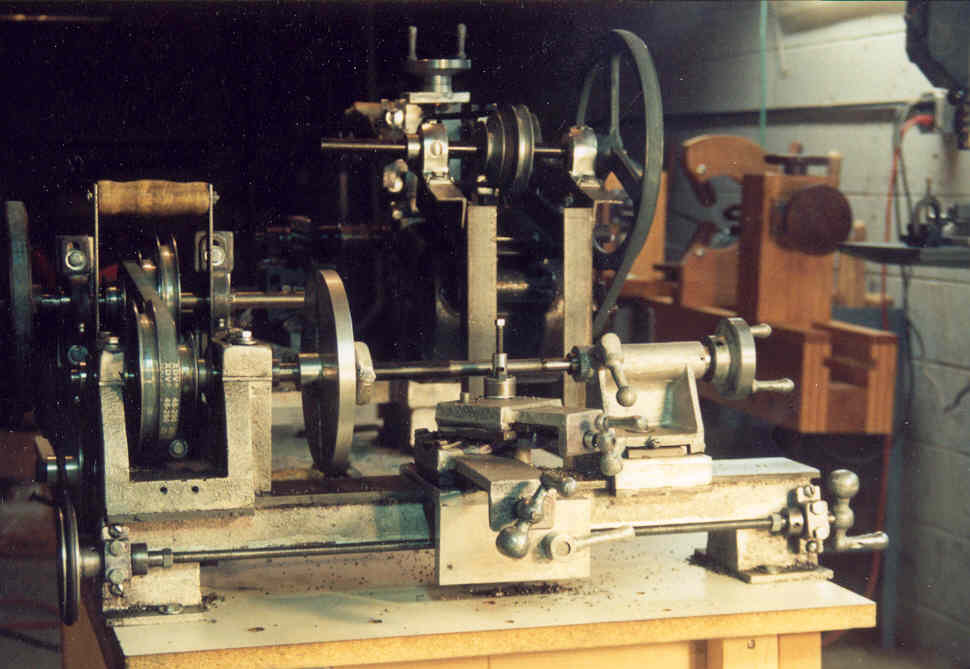

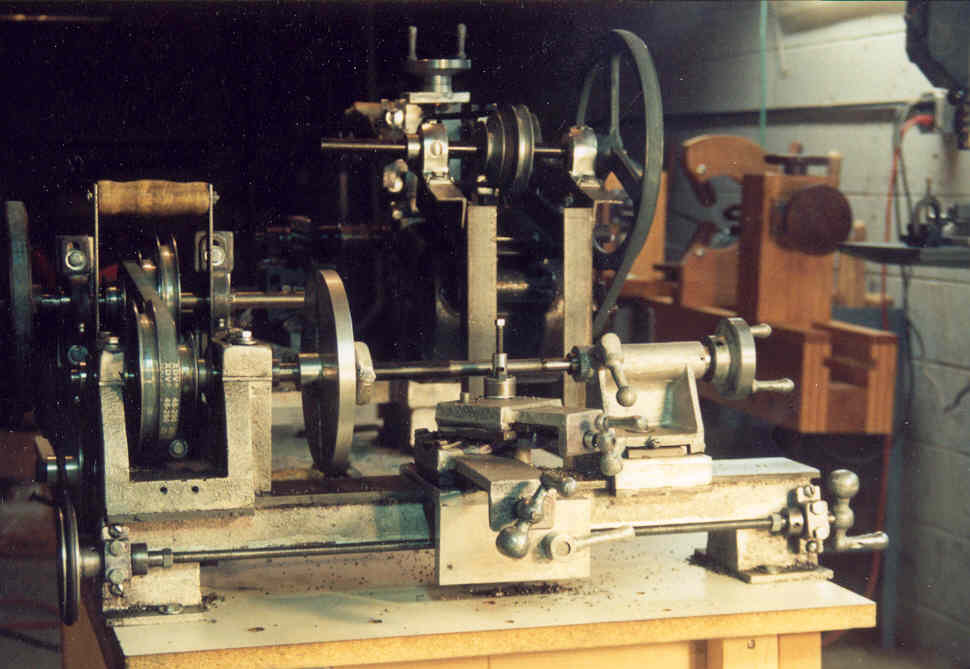

Gingery lathe in the foreground, Gingery mill and homebuilt wood lathe in background.

Turning on centers with lathe dog.

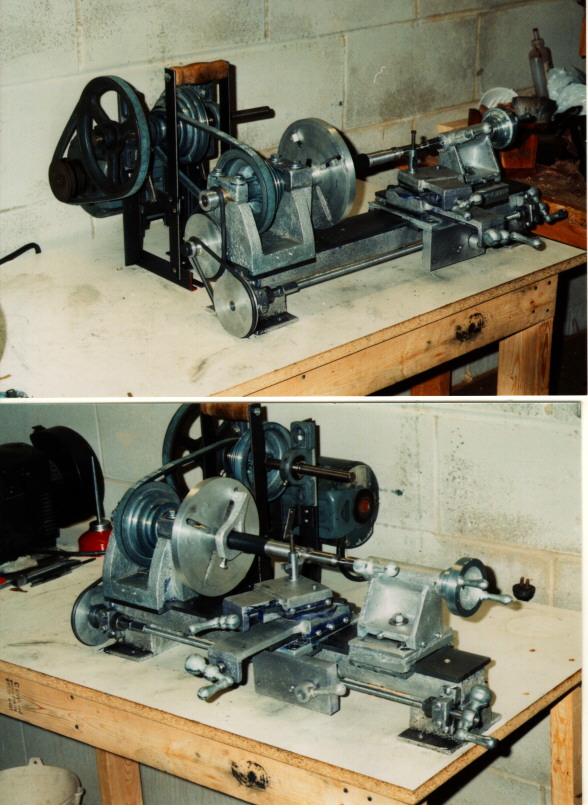

Wooden patterns used to create the sand molds to make lathe parts

Patterns for 4 jaw chuck, 2 jaw chuck and steady rest.

Copyright © 2003, David B. Doman PhD, All rights reserved.